TURNER PRIZE ARTIST – LUBAINA HIMID – VOW ART

‘Telling stories of the black experience that are both everyday and extraordinary is what I’m here to do’

The Turner Prize winner talks to Tate Modern’s Zoe Whitley about black visibility, historical trauma, and the power of the ordinary in her paintings

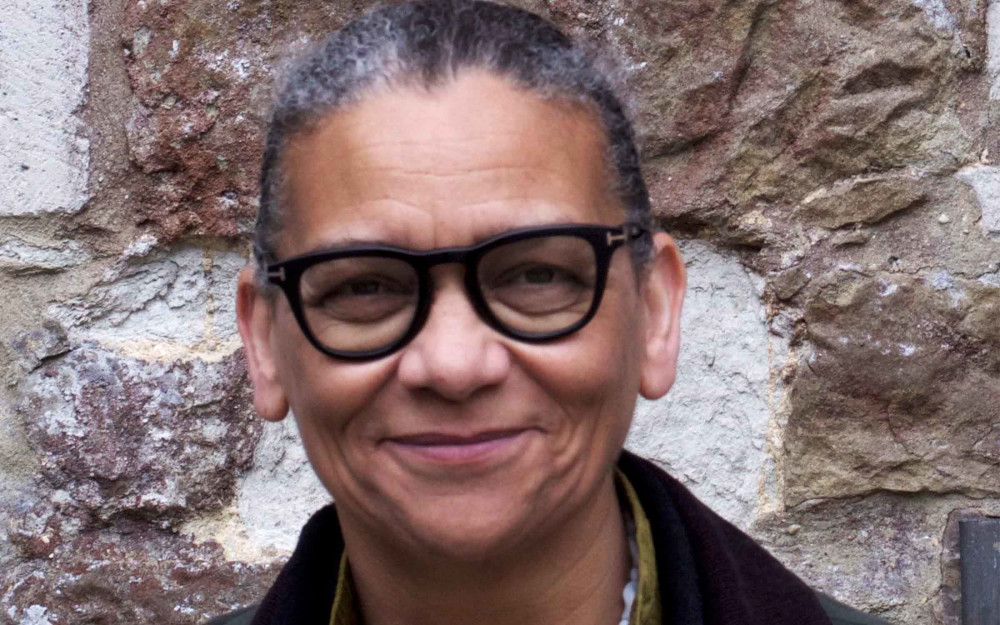

Lubaina Himid. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

interview by Zoe Whitley

Zanzibar-born. Theatre design-trained. Royal College of Art graduate. British contemporary artist and curator. Professor. Politically driven. First black woman and oldest artist to win the Turner Prize. You’ve been defined by so many descriptors in the press recently. But how do you define yourself?

The simplest answer is: ‘I’m an artist who happens to do all these other things.’ So those other definitions don’t sit easily. I approach everything – even teaching – as an artist first. I think, strategically and politically, I would have said at one point: ‘I’m a black woman artist.’ That’s still absolutely a correct definition. But I’m trying to move toward that happy day when we don’t have to do that. Although I would never want to abandon that as a description either.

The word I most often use for you is ‘painter’. Your practice as a painter is one I consider to be particularly rich. You absorb into painting a range of media typically found throughout your oeuvre in sculpture, installation, and assemblage. Paper and canvas are not the only fair game, but also plywood, found objects, banknotes, porcelain…

I think of my work the way I think of performance, theater, or opera. It can exist without someone looking at it, but it doesn’t really work unless an audience is exchanging something with me. I want to introduce a greeting to the visitor. Most people who come into the viewing space know what a plate is, or a tureen, or a banknote. That’s one of the reasons I use those kinds of things to make paintings with.

My work isn’t about being distant and admired. It’s about trying to broker a deal, open a conversation. It’s not about making something that is grand and mysterious. There’s plenty of mystery in the everyday. The more you know how something is put together, the more you can marvel at it, really. I want to make something that is sort of incredibly ordinary. And out of that comes some mysterious and special things.

Lubaina Himid, Man in a Jumper Drawer, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens.

The drawers are a good example…

If you open a drawer in your own space, you aren’t expecting any surprises. But if you open somebody else’s drawer, you don’t know what’s inside. When you buy secondhand furniture, there’s a trace of other lives – other people polishing it, other people lining the drawers with paper the way my mother used to do. I want that feeling of other lives residing in that ordinary thing. There’s something hidden within.

You often work in series. How does revisiting a theme – whether it is drawn from the history of art or current events – allow you to convey your perspective?

No issue, series of events, or time in history is ever simple. I’m often talking about narratives where a gap needs filling in an enormous history. The device of six or nine works involves shifting emphasis with each piece in the series. There are now six Le Rodeur paintings, which are, in a sense, giving an opportunity to watch a drama unfold. I keep trying to get to the bottom of this question of how much past historical trauma is vibrating around, say, the buildings that were built with the wealth of that time. That atmosphere lingers. What does it do to us as protagonists within those spaces?

The latest [in the Le Rodeur series] – and I think it will be the last – is the sixth painting, called Ball on Shipboard [2018] after the James Tissot painting of the same name. Aboard a pleasure steamer are seven men. There’s a party going on below deck. Six men are on deck and there’s a rower out at sea. The men are all observing.

It can be easier for men to have public conversations that are observed without them becoming objectified. These men are being intimate with each other, standing very close to one another, in a way that men often aren’t in public. I’m trying to throw out questions about who can be represented in paintings and what they can do.

Lubaina Himid, Ball on Shipboard, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens.

You’ve spoken about what it means to be unseen, unrepresented, or misrepresented in daily life. You once said: ‘If you don’t see yourself on the TV, in the art gallery, or in the newspapers in any form except as a criminal, then that’s hard. If you’re creative then you try to make or sing or build your way out of that.’ Let’s talk about your ongoing series based on content from The Guardian newspaper.

When I talk about this series with people younger than 25, they cannot fully comprehend that in as little time ago as the mid-1980s, it was incredibly difficult to see yourself in popular media as a black person. It just didn’t happen. We weren’t in advertisements, in the newspaper, on the TV, or anywhere. It was said that if they put us on the cover of glossy magazines, the magazines wouldn’t sell. The more you hear that, the more it is embedded as a cultural fact. It led to an objectifying obsession with the black body. We were exotic but never seen as ordinary. It was a bleak time.

If you were in the business of visualizing, it seemed fundamental that artists were the people to turn that around. So I asked myself: ‘What does my life look like? How does the political crash into my personal life?’ I need to be able to see myself. I need to make paintings that feel like what it means to be me. We need to feel we belong in those shared spaces. Telling stories of the black experience that are both everyday and extraordinary is what I’m here to do.

Lubaina Himid, Negative Positives: The Guardian Archive, 2018 (detail). Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens.

Ever since the pioneering exhibitions you curated throughout the 1980s, you have always established routes to support and champion other black, and specifically women, artists. A recent New York Times profile heralded your radical generosity toward other artists even while you command solo exhibitions at international institutions. What role does being part of a community of artists play in your life?

I was always going to do that. I’m not afraid to speak out. I was trained as a designer rather than an artist, so I’m used to negotiating. I also make work outside of London. That’s where I do my thinking and testing. I know there are other people out there, near at hand in this small city I live in, holding similar political perspectives. We know others are out there doing this work in different ways. I don’t hold with the idea that you can make really connected work if you see yourself as the only person.

When I look at my finished work, I know who helped me make those things – their energy, their problem-solving, let alone their sheer hard graft. I don’t see myself as this one individual person. And that’s not some high moral ground – I just need to talk to people who are like me. As an only child, I’ve always made the decision to get outside of myself, to connect with other people. It’s why I don’t mind people coming to the studio or talking to me about what I’m doing while I’m doing it. My studio is not a sacred space – it’s a place where I meet people and exchange.

What continues to motivate you working as an artist day in, day out?

There are things I still want to say. Without being morbid, there are 63 years behind me, not 63 ahead of me. I take more risks with subject matter, materials, and the extent to which I can push the viewing space past the point of passive consumption. I want to create a real opportunity to feel and perhaps shift something in the viewer’s mind. Then they might shift something beyond the viewing space that they didn’t feel they could shift before they came in the space.

This interview – conducted on May 15, 2018 at Tate Britain, London – was edited and condensed.

Dr. Zoe Whitley is Curator, International Art, at Tate Modern, London.

Lubaina Himid's work is presented by Hollybush Gardens in the Feature sector of Art Basel in Basel. Feature is dedicated to curated projects by established and historical artists. Participating galleries in 2018 include: Galeria Raquel Arnaud (Arthur Luiz Piza), bitforms gallery (Gary Hill), Galerie Bernard Bouche (Etienne-Martin), Bureau (Matt Hoyt,Patricia Treib), ChertLüdde (Franco Mazzucchelli), James Cohan Gallery (Lee Mullican), Monica De Cardenas (Alex Katz), Fonti (Salvatore Emblema), Galerist (Nil Yalter), Grimm (Elizabeth Price), Barbara Gross Galerie (Jana Sterbak), Hamiltons (Irving Penn), Hanart TZ Gallery (Nilima Sheikh, Qiu Zhijie), Hollybush Gardens (Lubaina Himid), hunt kastner (Dalibor Chatrný), Kalfayan Galleries (Yannis Tsarouchis), Galerie Lange + Pult (Olivier Mosset), Galerie Emanuel Layr (Stano Filko), Galerie Löhrl (Gerhard Richter), Jörg Maass Kunsthandel (Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Lyonel Feininger, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff), Galerie Max Mayer (Jef Geys), Galleria Lorcan O'Neill Roma (Rachel Whiteread), P420 (Paolo Icaro), Franklin Parrasch Gallery (John McLaughlin), Galeria Nara Roesler (Paulo Bruscky), Richard Saltoun Gallery (Helen Chadwick), Galerie Pietro Spartà (Gilberto Zorio), Supportico Lopez (Robert Watts), The Third Line (Fouad Elkoury), Upstream Gallery (Marinus Boezem), and Galerie Zlotowski (Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel).